Our friends at Riverford have launched a petition here calling for the government to step in and protect Britain’s broken food system as part of their #GetFairAboutFarming campaign. Problems of fairness (or unfairness) in the food supply chain have now become so obvious that over the summer the EFRA Committee launched an inquiry into issues from ‘farm to fork’.

They said they wanted to investigate how profitability and risks are shared through the food supply chain, and whether existing government systems of monitoring and regulation of these work. Forty-two organisations and individuals, including Better Food Traders, gave written evidence to the Inquiry into Fairness in the Food Supply Chain. While we wait to see if those submissions make any major difference to government policy, here is what we wrote:

1. To what extent is the UK’s food supply chain currently operating effectively and efficiently?

While the factors affecting recent food price rises and shortages are multiple (energy costs, fertiliser costs, worker shortages, driver shortages, grain disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine), two major structural factors are the UK’s centralised and just-in-time supply chain.

Locally-grown food has to travel through national logistics networks before it arrives on supermarket shelves, while we are also becoming ever more dependent on food imports and global logistics networks. The UK currently imports around 46 percent of the total food it consumes. When these networks and supply chains face problems, food prices go up and shelves are left empty.

Over 90% of the food retail market is controlled by just nine supermarket chains resulting in an inefficient supply chain that causes GHGs (through refrigeration and food miles travelled to warehouses), traffic congestion, high levels of food waste and heavy use of plastic packaging.

The power imbalance between large retailers and their suppliers results in both unfair price negotiations and restrictive product specifications (size, shape, appearance – often unrelated to taste, nutrition or quality) that drive inefficiency and waste. These demands lead to excessive chemical use, farm-level food waste and loss of income for producers.

Up to 13 million tonnes of food are estimated to be wasted in the UK annually, costing businesses and citizens approximately £19 billion a year. Some 36 million tonnes of CO2 emissions domestically and overseas are the result. Yet the UK government, and the devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, have been slow to implement mandatory food waste reporting legislation for all medium and large food businesses from farm to fork.

2. How could structural relationships between farmers and fishers, food producers and manufacturers, handlers and distributors, retailers and consumers be improved for both domestic and foreign foods?

Better Food Traders would like to see structural relationships improved through government policy that prioritises decentralised, regional food supply: greater food production in all regions of the UK (ideally organic and regenerative), shorter supply chains, and more local, independent food retailers.

Several reports recognise that direct sales and short supply chains are a tool for improving the position of the farmer. A survey of 500 farmers by Sustain in 2021 found that only 5% of farmers would ‘prefer’ to sell to a supermarket, processor or manufacturer, with the top three preferences being a food hub such as a Better Food Trader (55%), direct sales (36%) and food service (29%). 56% of respondents said they wanted to supply into a different market and a further 20% said they would consider supplying into a different market.

The opportunities that farmers see in those preferred markets include: a better price (75%), ability to sell large quantities of produce (49%), business resilience and stability (42%), better market control (38%), direct links to customers (31%), and supporting future climate and nature ambitions (30%).

We echo our partners Sustain in making three recommendations to Government:

- Tougher regulation is needed to help redress the imbalance of power between farmers, processors and the supermarkets including maintaining the Groceries Code Adjudicator; introducing new, legally binding, sectoral supply chain codes of practice; better labelling to ensure transparency; and planning rules to curb large retail dominance.

- Build new and better routes to market for farmers – so they have more power and gain greater value from their produce – through an action plan to increase the market share of shorter and farmer-focused supply chains; public investment in localised agri-food infrastructure (such as sorting, drying, hubs) and enterprise; and using dynamic public procurement models to source from a large range of UK farmers and growers.

- Create more transparency in supply chains, with greater mandatory reporting and acknowledgement of the huge overheads in the current, complex system.

3. How does the market power of UK supermarkets and manufacturers compare to other participants in the food supply chain, and how does this compare to equivalent relationships in other advanced economies?

A very small number of retailers and manufacturers hold the power in price negotiations in the UK. The prices paid to British farmers by supermarkets are often so poor that farmers are virtually subsidising supermarkets and their shareholders.

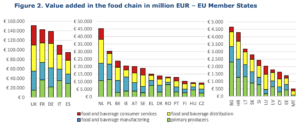

This inequality is not unique to the UK but we have one of the worst situations for farmers and growers in Europe. A low proportion of economic value added goes to primary producers in the UK; a large proportion goes to distributors, and the highest proportion in Europe goes to ‘food and beverage consumer services’ ie retailers.

Better Food Traders supports and promotes local, independent food retailers. Many of these are producers and/or processors who sell to customers directly, eliminating inefficient distribution and redressing the power imbalance in the value chain.

Such retailers are able to sell food that is fresher, less processed, has travelled far fewer miles, and does not come with the issues of trust and ethics seen in opaque, global supply chains.

Better Food Traders also pay better wages. Over 40% of food workers are on the minimum wage or less, compared to an 8% average across the UK economy, whereas all Better Food Trader members pay the Living Wage to all staff. The worker shortage will not improve unless pay and conditions become more reasonable in this sector – and that relates to the overall value chain, costs, and allocation of profits to shareholders.

4. What is the relationship between food production costs, food prices and retail prices? How have recent movements in commodity prices and food-price inflation been reflected in retail prices?

Farmers and food suppliers are doing what they can to mitigate rising costs, but they are being asked to absorb a disproportionate amount of the pressure and risk in the supply chain.

A recent report by Promar International found that growers’ cost of production has increased by 27% in the 12 months to Autumn 2022. Diminishing margins of primary producers are leading to business closures and restructuring in the horticultural sector, which has already seen a decline in production by as much as 20-30%.

Last week the Competition and Markets Authority published its initial report on food price inflation and concluded that price rises have not been driven by competition issues, and both operating profits and margins in the retail grocery sector have fallen, due to retailers being restricted in their ability to raise prices without losing business. Retailers’ costs have been increasing faster than their revenues, indicating that rising costs have not been passed on in full to consumers. And while margins are falling for retailers, they are plummeting for producers.

A report by Sustain/University of Portsmouth – deliberately using data from before the Ukraine invasion – found that even before that crisis, farmers were often left with less than 1% of profits when supplying a supermarket chain. The vast majority of profits are directed to intermediaries like processors, transport companies, retailers, and shareholders.

By contrast, in shorter routes to market – by selling through a local Better Food Trader or a non-profit wholesaler like the Better Food Shed – more value reaches farmers and their workers. The same report found that three times more profit goes to farmers with every purchase made from a local Better Food Trader. Farmers make more money selling into this transparent, ecological supply chain, which they can then invest in their businesses – sustainable businesses that are the future of farming and our countryside.

Independent SME retailers such as Better Food Traders also make larger socio-economic contributions to their local communities in relation to their size. For example, SME bakeries support more jobs per loaf, and research has found that SMEs employ a full-time employee for every £42,000 of turnover, compared to £124,000 in a supermarket.

Investment in better food enterprises and a more diverse supply chain is much needed – through public funding for infrastructure, Local Planning strategies, and fiscal measures to help existing and new SME food businesses thrive.

It is also worth noting that where food production is reliant on chemical inputs and long journeys, food prices will be more affected by rising fertiliser costs and fossil fuel price increases. There is growing evidence that organic/agroecological produce is becoming more affordable and competitive over time, and an ongoing study by the Organic Research Centre hopes to shed more light on this later in the year.

5. Does the structure of the UK food supply chain support overall domestic food security (both self-sufficiency and the availability of imported foods)?

The UK relies heavily on food imports. In 2020, the UK imported 46% of the food it consumed, with 28% of the UK’s food imports coming from the EU, and Africa, Asia, and North and South America each providing just over 4% of the food consumed in the UK. As climate change makes food production in Europe more difficult, imports from the EU are likely to become less reliable and more expensive.

The fruit and vegetables category has the largest trade deficit. In 2021, imports were £10.5 billion while exports were worth £0.9 billion, giving a trade gap of £10 billion.

In 2020, the Climate Change Committee warned that land inefficiency was having an impact on food security, climate and public health, citing a 2017 study that illustrates the relative land inefficiency of producing livestock products:

- In 2010 only 15% of UK agricultural land area was used to grow crops that are directly for human consumption with a further 22% to grow livestock feed crops. Grassland for livestock accounted for the remaining 63% of agricultural land.

- 85% of the land footprint used to produce animal products contributed about 32% of total calorie supply and 48% of total protein supply.

- However, cropland and grassland should not be treated equally. In some regions, crops and livestock farming do not compete for the same land as many grassland areas (e.g. the uplands) are not suitable for crop production.

Domestic food security is unlikely to grow without a clear government strategy for increasing domestic supply, particularly of fruit and veg. Both Welsh and Scottish governments have realised the potential for government procurement as a lever for increasing supply of agroecological and local produce, and have started either to fund pilots (as in Wales) or to create supportive procurement frameworks or legislation (as in Scotland) to explore how local authorities can successfully procure more seasonal, organic produce.

In England there appears to be no real policy action. A very delayed review of improved procurement requirements and Government Buying Standards (GBS) is due at the end of the summer. However, GBS does not apply to education, which accounts for 60% of the 4 billion that is spent on food and drink by the government.

If you would like to show your support for farmers, sign the petition now.

Photo credit: Riverford – Guy Singh-Watson is heading up a campaign calling for fairer treatment for farmers.